- Details

How cola still tingles after a year

When you add energy to gases or gas mixtures, a plasma can be created, and inside it things go haywire: atoms turn into ions, free electrons whiz through space and collide with everything, some ingredients decay, other substances form anew. Depending on what is added to the starting material, plasmas can therefore be used to produce larger compounds. Hydrocarbons and silicon hydrogens are turned into long chains of molecules called polymers.

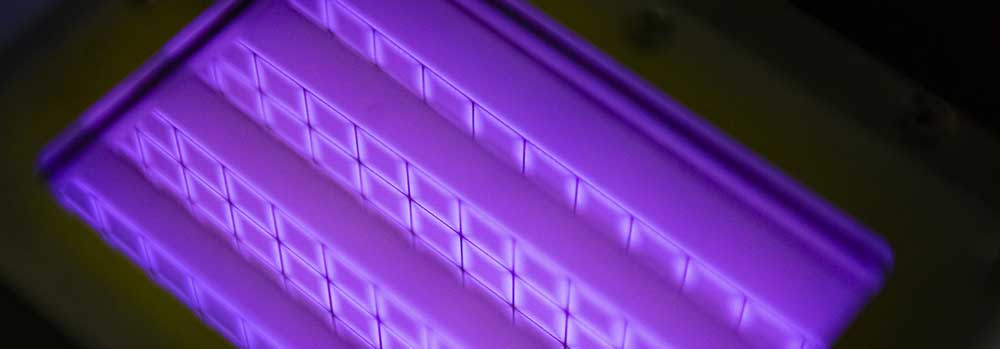

“If you want to etch with plasmas that tend to form polymers, it’s bad because the nanoparticles that form are a hindrance,” explains Professor Peter Awakowicz, holder of the Chair of General Electrical Engineering and Plasma Technology at RUB. But his team has taken advantage of the situation. If polymers are specifically made to form and deposit on the surfaces surrounding the plasma, they can be coated in a targeted manner. Thanks to this so-called Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition, or PECVD for short, it is possible, for example, to apply ultra-thin, gas-tight coatings to the inside of PET bottles, ensuring that the contents last longer, or to protect organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) from moisture so that the TV screens work for a long time. This and much more is only possible because the plasmas are cold and thus do not damage the PET bottle or other surfaces to be coated with heat. Only the fast electrons in the plasma are hot, and they do not damage the surfaces.

Making milk and medicines last longer

The glass-like coating of the plastic, which is only 20 to 30 nanometres thin, ensures that 10 to 100 times less gas escapes through the bottle. This extends the shelf life of a soda pop from the previous four weeks to about a year. The method is also of interest for the packaging of milk and other foods, as well as medicines and even microelectronic components.

“This type of coating is also environmentally friendly, because the tiny amount of material can simply be neglected during recycling,” explains Dr. Marc Böke from the Experimental Physics II department at RUB. Composite materials made of plastic and aluminum, such as Tetrapaks, are far more difficult to recycle because it is very difficult to separate the components.

Other applications of the PECVD method can be, for example, the coating of implants that grow into the bone better than conventional ones. There are also many microelectronic applications. For example, transistors can be deposited with ultrathin silicon dioxide films in plasma.

Oxygen tips the scales

The challenge lies in controlling the formation of the layers. “The layers should not only be ultra-thin, but also absolutely dense, gap-free and uniform,” explains Marc Böke. The adjusting screws for this are manifold. For one thing, it depends on the gas mixture. Atomic Oxygen is a particularly important player. Its proportion can be used to control, among other things, whether other additives evaporated into the plasma form inorganic layers, such as the glass-like silicon dioxide, or organic layers that have other interesting properties, such as giving surfaces greater biocompatibility or enabling gas separation.

The pressure at which the plasma is operated is also significant. Higher pressures and corresponding gases result in the coating of surfaces, while lower pressures are more likely to result in etching processes, which are central to all microelectronics (from cell phones to modern cars). Similarly, the geometry of the reactor and the choice of energy source influence what happens in the plasma and how it affects the surrounding surfaces. For example, an appropriate plasma can be ignited by microwaves, but also by inductively or capacitively coupled radio frequency. “In general, different sizes of plasma reactor are possible, up to the huge dimensions needed to coat entire window panes for high-rise buildings,” says Peter Awakowicz. These coatings serve to reflect infrared radiation that would otherwise cause it to get as hot behind them as in a greenhouse when the sun shines. But you can still see through it. With the sputtering of thin metal layers on foils used for this purpose, it is also possible to work in a feed-through process and thus coat many square metres.

Measurement techniques had to be developed

Only after the basic mechanisms of high-power pulsed sputtering (HiPIMS) and PECVD had been measured and understood in the first phase of the Collaborative Research Center SFB/TR 87 the research teams could get down to the business of implementing such large-area coatings. “We had to develop the appropriate measurement techniques in some cases,” Awakowicz recounts. “If you simply hold a measuring probe in the plasma, it may become coated itself and may lose its function,” he gives an example.

The researchers have gradually been able to fathom and perfect many aspects of the possible processes. For example, PET bottles are cleaned and activated before coating, also by means of plasma. But here, too, the surface of the bottle changes, which in turn influences the subsequent coating. Measurements of the particle flows during cleaning revealed what happens in the process: is wettability increased? And if so, how? Does the surface energy change? At what point in the treatment does the surface become roughened? “If the surface is too rough, you can no longer cover it evenly with an ultra-thin coating,” explains Marc Böke. If all these aspects are taken into account during cleaning and the process is run optimally, this has a considerable influence on the success of the subsequent coating: “We were able to increase the impermeability, which was initially a factor of 100 (depending on the substrate material), to a factor of 500 through the correct setting of the previous cleaning,” says Peter Awakowicz.

Keeping plasticizers away from food

Detailed knowledge of the processes in the plasma and the resulting coatings now also make it possible to coat stretchable films with gas-tight thin films. Thanks to an intervening buffer layer, Marc Böke’s team was able to increase the tolerance of the layer to the stretching of the film from originally about three to about six percent. This application is also of interest to the food industry, for example, as the dense coating prevents ingredients from the film, such as the dreaded plasticizers, from penetrating the food.

The latest application, which is currently being worked on, makes a virtue out of necessity: if one actually wishes for layers that are as dense and defect-free as possible, defects such as tiny pores in the coating are almost impossible to avoid. They allow the research teams to use plasma coating to develop non-swelling filter membranes that exhibit previously unknown properties. They can desalinate water or separate gases from each other, such as oxygen from CO2. “Normally, the more selective a membrane is, the lower its transmission, i.e. the more inefficient the process,” explains Marc Böke. “With plasma coating, however, we can control pore formation so that selectivity no longer comes at the expense of transmission or efficiency.” The researchers of the SFB/TR87 can simulate and tailor the polar properties of the membrane. This makes it easier for certain molecules to pass through the membrane. “Water molecules, for example, are made to give up their actual angle, practically flattening out and thus sliding through the pore,” Peter Awakowicz describes. “You couldn’t target something like that before.”

adapted from Meike Drießen (RUB)

- Details

Plasmas aid in wound healing, cancer therapy and pollutant degradation

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) have different functions in biological contexts: At low concentrations they act as signalling substances, for example in wound healing. At high concentrations they destroy biomolecules, an effect immune cells use to kill pathogens. Non-equilibrium plasmas, in which the electrons have high temperatures but the gas temperature remains low, can produce such RONS without heating the treated samples. These non-thermal plasmas are already being used for sterilisation purposes. Their therapeutic use in wound treatment and cancer therapy is currently being explored.

In ten years, we will understand in more detail the mechanisms underlying the generation of the different reactive particles in plasma as well as their biological effects. Based on this knowledge, plasma reactors can then be designed that provide RONS at concentrations and with mixing ratios required for specific applications – such as reactions catalysed by enzymes that utilise plasma-generated species or the degradation of pollutants through the joint action of plasmas and microbes.

by Julia Bandow (RUB)

- Details

What exactly happens at the interface between plasma and surface

Plasmas have been used in industry for decades with great success. However, in many cases their application is based on trial and error. A deeper understanding of the processes that take place in the excited gases, sometimes in a very short time and on tiny length scales, has been largely lacking until now. Researchers from Bochum and Ulm are venturing into this new territory together in the frame of the Collaborative Research Centre 1316 “Transient Atmospheric Pressure Plasmas: From Plasmas to Liquids to Solids”.

Their fields of work are complementary: Professor Thomas Mussenbrock, who holds the Chair of Applied Electrodynamics and Plasma Technology at RUB, focuses on the plasma as a whole, whereas Professor Timo Jacob, head of the Institute of Electrochemistry at Ulm University, specialises in atomic processes. “We calculate processes at different ends of the time and length scales and try to fill the gap in between,” as Mussenbrock recaps.

Complicated molecules

Timo Jacob is the expert for interfaces between plasmas and their environment. This interface can be between plasma and solid, but also between plasma and liquid. “If we want to use plasmas to coat a surface or to change its structure, we have to understand the interaction between the plasma species and the surface on an atomic scale,” he explains. This process seems simple and predictable. But his team goes into much more detail, because complicated molecules can also form in plasmas, which are present in specific excited states. They can then change both the properties and the structure of catalytic surfaces or even actively impact reactions at the interface directly. Until now, such details had been little understood. “We had to develop the tools for this first,” says Jacob.

He and his team established methods that can describe how the plasma changes the molecules during a reaction. The influence of the molecules, for example, can result in an effect on the interface that becomes meta-stable but of particular interest for catalytic reactions.

The effort usually increases cubically

The processes calculated in this manner take place on the Ångström or nanometre scale within a tiny fraction of a second. The fewer effects the researchers have to calculate simultaneously, the more accurate the simulation can become. “Our highly accurate calculations involve a maximum of 300 to 400 atoms; using semi-empirical dynamic simulations even several 100,000 atoms are possible,” explains the researcher. “We sometimes use specifically acquired computing clusters or mainframes at high-performance computing centres for this purpose.” The effort usually increases cubically: i.e. if twice as many atoms are to be included in the calculation, the computational effort increases eightfold.

The fundamental insights thus gained should help, for example, to make plasmas usable for new applications – most importantly, catalytic processes. The researchers concentrate on both the reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) and the decomposition of relatively simple hydrocarbons as a model, using n-butane as an indicator.

Data is extremely scarce

It is of course not enough to consider only a few hundred atoms. This is where the research of Thomas Mussenbrock’s team completes the overall picture. His length scale is a billion times larger than Jacob’s. Quantum mechanical effects that are important at the atomic level no longer need to be explicitly considered in this case. The idea is to map plasma dynamics and plasma chemistry. “We look at the plasma based on classical physics.” The methods for this are known and well understood, but the needed data is extremely scarce.

A major challenge is that industrial processes with plasmas should take place at atmospheric pressure, if possible, and preferably at air pressure. “At this relatively high pressure, many interactions come into play,” explains Mussenbrock. What reacts how strongly with which molecules and atoms? Based on the results of Timo Jacob’s calculations, his team scales up the simulation. The results can be matched with experiments – deviations must be understood and explained.

“Bringing the two ends of the time and length scales together is uncharted scientific territory,” points out Thomas Mussenbrock. Consequently, the teams are breaking new ground. Perhaps at some point, thanks to their findings, it will be possible to make large-scale industrial processes such as ammonia production more energy-efficient.

adapted from Meike Drießen (RUB)

- Details

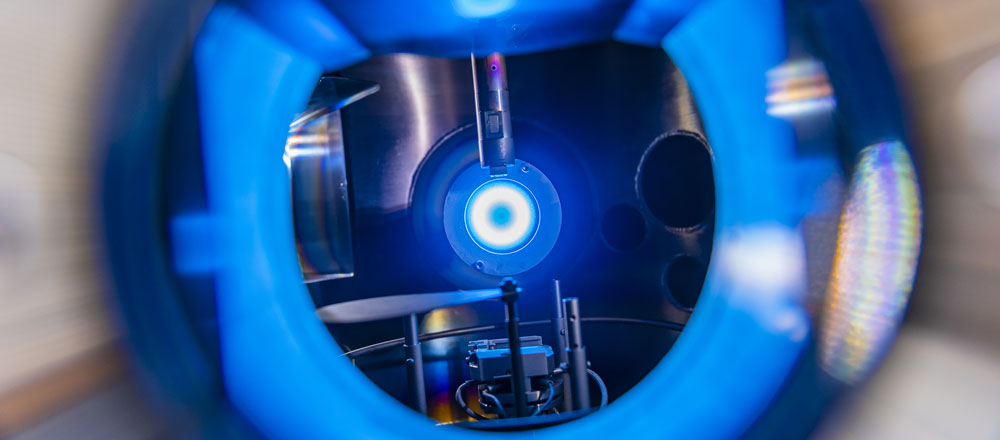

A sphere that makes electrons oscillate

Plasmas play a vital role in many industrial applications. The energetically excited gases can be used, for example, to deposit coatings on surfaces, such as scratch-resistant protective layers on plastic spectacle lenses, or high-precision optical filters on quartz glass. In the process, the plasma is used to bombard the coatings that grow on the substrate by vapour deposition with ions, thus effectively hammering them into place.

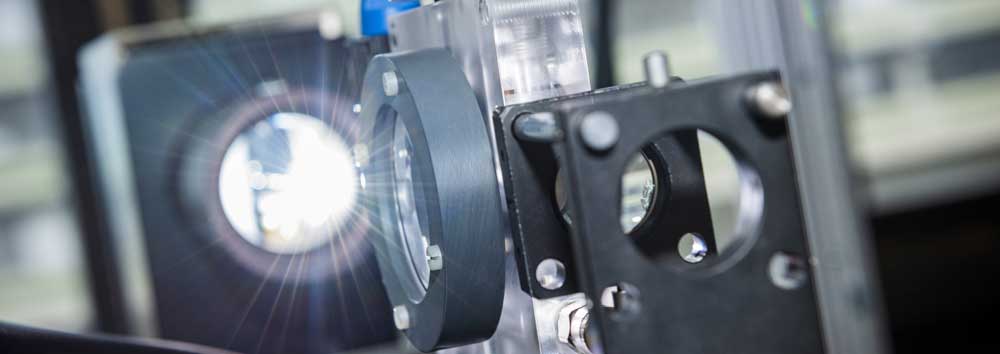

But such processes must meet many requirements. For example, they must take place at low temperatures to prevent damage to the coated surfaces. “In modern production processes, more and more emphasis is also being placed on precision,” stresses Professor Ralf Peter Brinkmann, who holds the Chair for Theoretical Electrical Engineering at RUB. All resulting products must be exactly the same, and the coating must be defect-free. To achieve this level of precision, it is necessary to constantly monitor the plasma. The electron density is particularly important in coating processes. If it were to fluctuate too much, this would negatively affect the quality of the finished coating. “Ideally, the electron density should be constantly measured and automatically readjusted if necessary, so that no human has to interfere in the process,” explains Brinkmann.

Small, reliable, maintenance-free

A measuring instrument that can do all this has to meet a variety of requirements: It should be as small as possible, reliable, maintenance-free, and it must neither interfere with the coating process nor be damaged in the plasma. Experts refer to this as “process-compatible plasma diagnostics”.

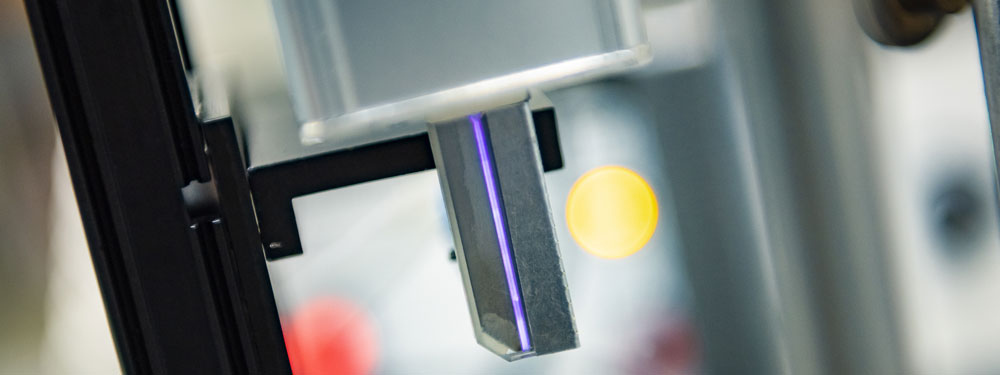

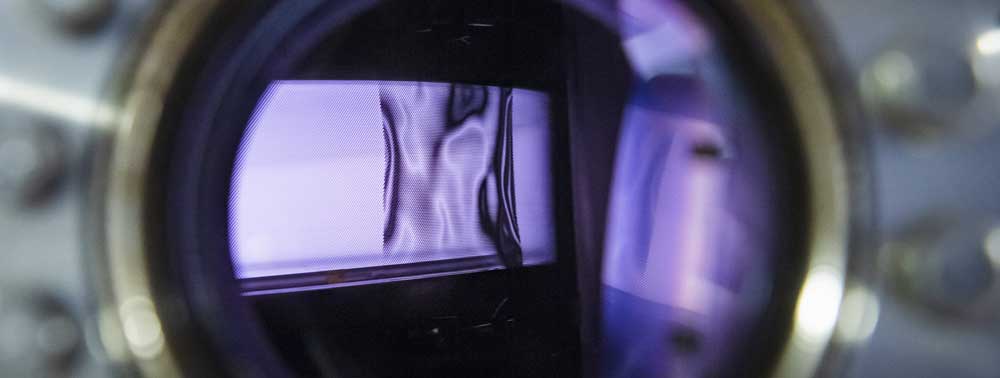

Researchers have been pursuing one idea for a long time: The electrons, which move freely in the plasma, can be made to oscillate by applying a small external voltage. If the right frequency is hit, a detectable resonance occurs. Since the resonance frequency depends on the electron density, this can then be theoretically calculated.

Picture this like driving an old car.

– Ralf Peter Brinkmann

However, earlier attempts to put this idea into practice encountered some difficulties. A Japanese research group, for example, proposed a very simple construction: The team used a coaxial cable, similar to an analogue antenna cable, allowed the inner conductor to protrude a little, and inserted the end of the cable into the plasma. If a voltage was applied, resonances of the plasma could be measured. However, resonances of equal value occurred at several different frequencies – a veritable zoo. “The problem was: which one should be used for diagnostics,” explains Ralf Peter Brinkmann.

Analyses by the Bochum-based researchers provided an answer to the question of where the different resonances came from: As simple as the design of the measuring equipment was, different oscillations with different resonance frequencies arose at different sections of the apparatus. “Picture this like driving an old car,” as Ralf Peter Brinkmann illustrates the principle. “At a certain speed, the exhaust rattles, at another, it’s the wing mirror.”

The more symmetrical, the better

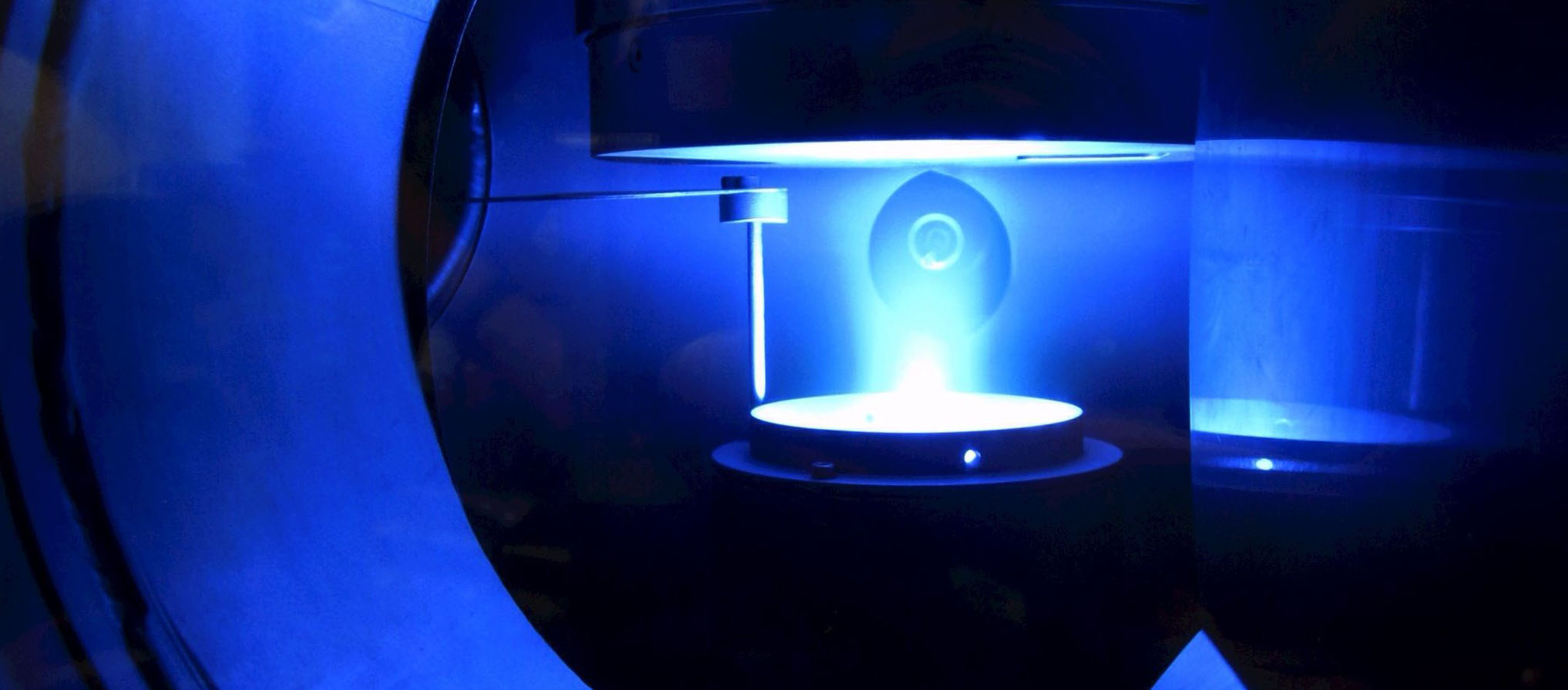

To remedy the situation, the team devised a concept that aimed for the simplest possible oscillations. Their aim was: the more symmetrical, the better. “The spherical shape is the simplest configuration imaginable,” says Brinkmann. “A floating marble would’ve been our first choice.” However, it was not quite that simple, of course. Electricity always needs a forward and a return conductor. Accordingly, two metallic hemispheres were chosen. The construction is rotationally and mirror-symmetrical, both electrodes are the same size. “Here, too, we measure resonances at different frequencies,” explains Ralf Peter Brinkmann. “But they can be clearly sorted. The strongest resonance is the dipole resonance; the other, weaker ones, represent the overtones to this keynote, so to speak.” The name “multipole resonance probe” (MRP) was derived from the mathematical method of “multipole analysis” used for this purpose.

The reason why researchers opt for the MRP is that the relationship between plasma density and resonance frequency is given by a simple mathematical formula. The plasma density is the only unknown in this equation. Once the equation is solved, it can be calculated from the measured values. “This means that it is not necessary to calibrate the measuring probe before use, i.e. to compare it with other measured values,” elaborates Ralf Peter Brinkmann.

Plasma was kept consistent through constant monitoring

So much for the underlying theory. For practical implementation, the researchers teamed up with three other chairs at the faculty. Professor Ilona Rolfes’ High Frequency Engineering Institute carried out a high-frequency optimisation of the entire system consisting of probe head and holder. For example, it was possible to make the holder practically invisible to the plasma. Professor Thomas Musch’s Institute of Electronic Circuits designed control electronics based on radar technology. And finally, Professor Peter Awakowicz’ Institute for Electrical Engineering and Plasma Technology tested the finished probe in a number of plasma processes.

The Federal Ministry of Education and Research funded the joint projects Pluto and Pluto plus to develop the MRP to the point where it could be used in practice. This also provided the opportunity to test the probe with industrial partners. And it turned out that if the electron density in the plasma was kept consistent through constant monitoring by means of MRP and automatic adjustment of the control, the fluctuations in the process results were significantly reduced.

Today, a spin-off is about to get off the ground.

adapted from Meike Drießen (RUB)

- Details

Where basic science meets technology

Plasma physics is the study of the behaviour of ionised gases. Statistical physics, fluid dynamics, electrodynamics as well as atomic and molecular physics come together to form a discrete discipline. Plasmas determine both stellar evolution on astronomical scales and etching of nanostructures in the semiconductor industry. Plasma-based engines are already powering satellites in space, and very hot magnetised plasmas may provide clean energy through controlled nuclear fusion in the future. Tiny cold plasmas at atmospheric pressure offer a wide range of applications, from CO2 conversion to medicine and biology. Major advances in measuring the internal parameters of plasmas and in their simulation have recently contributed to a much better understanding of these complex systems. Wherever the journey into the future takes us, it will not be without plasmas.

by Uwe Czarnetzki (RUB)

- Details

A reference source for plasma research

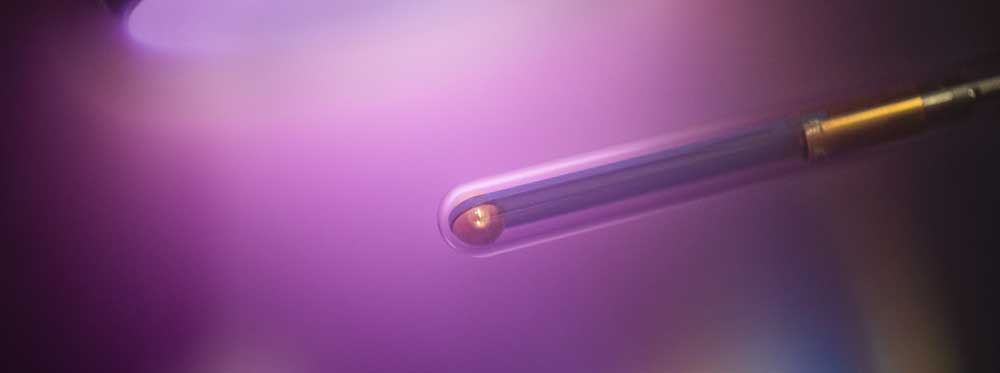

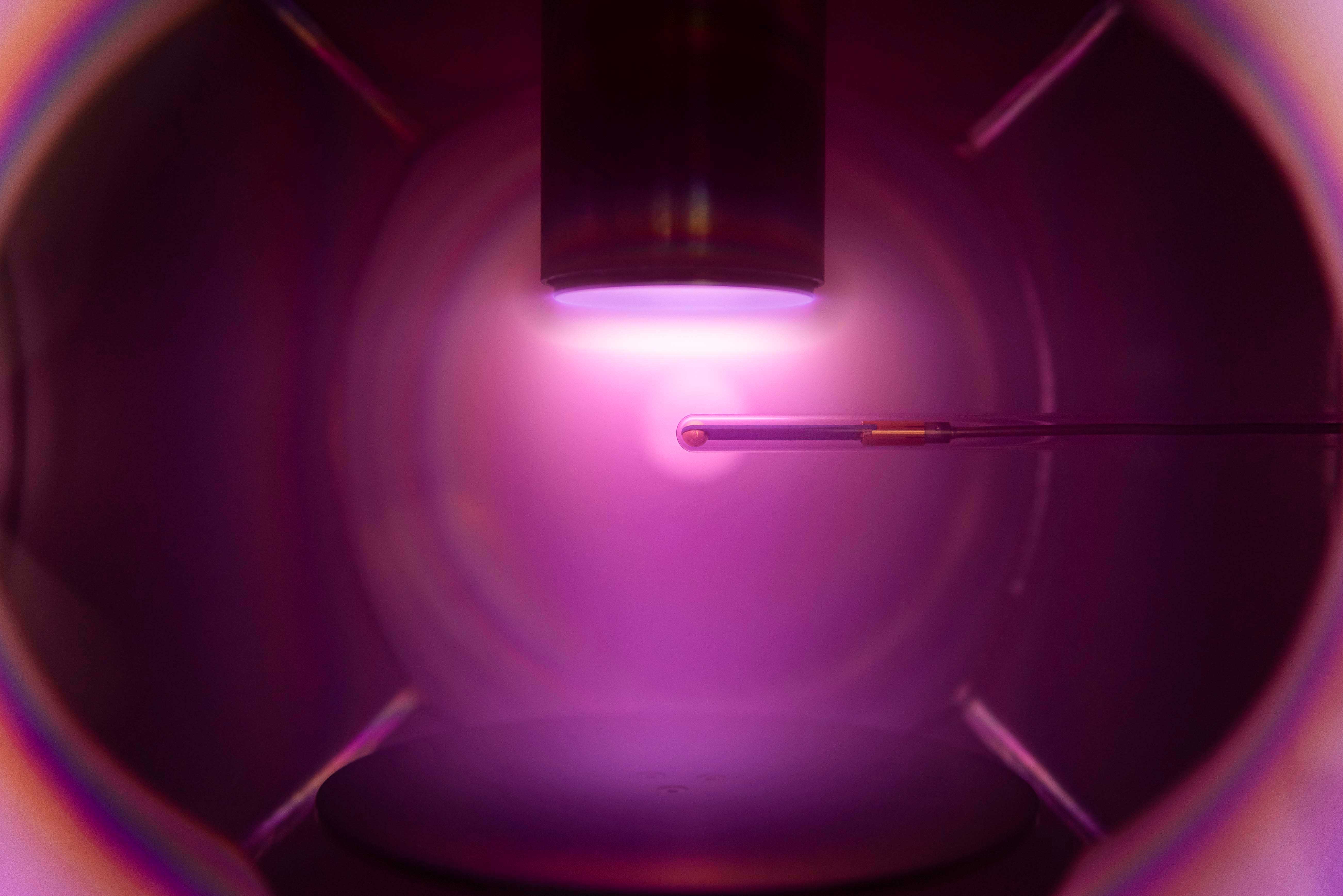

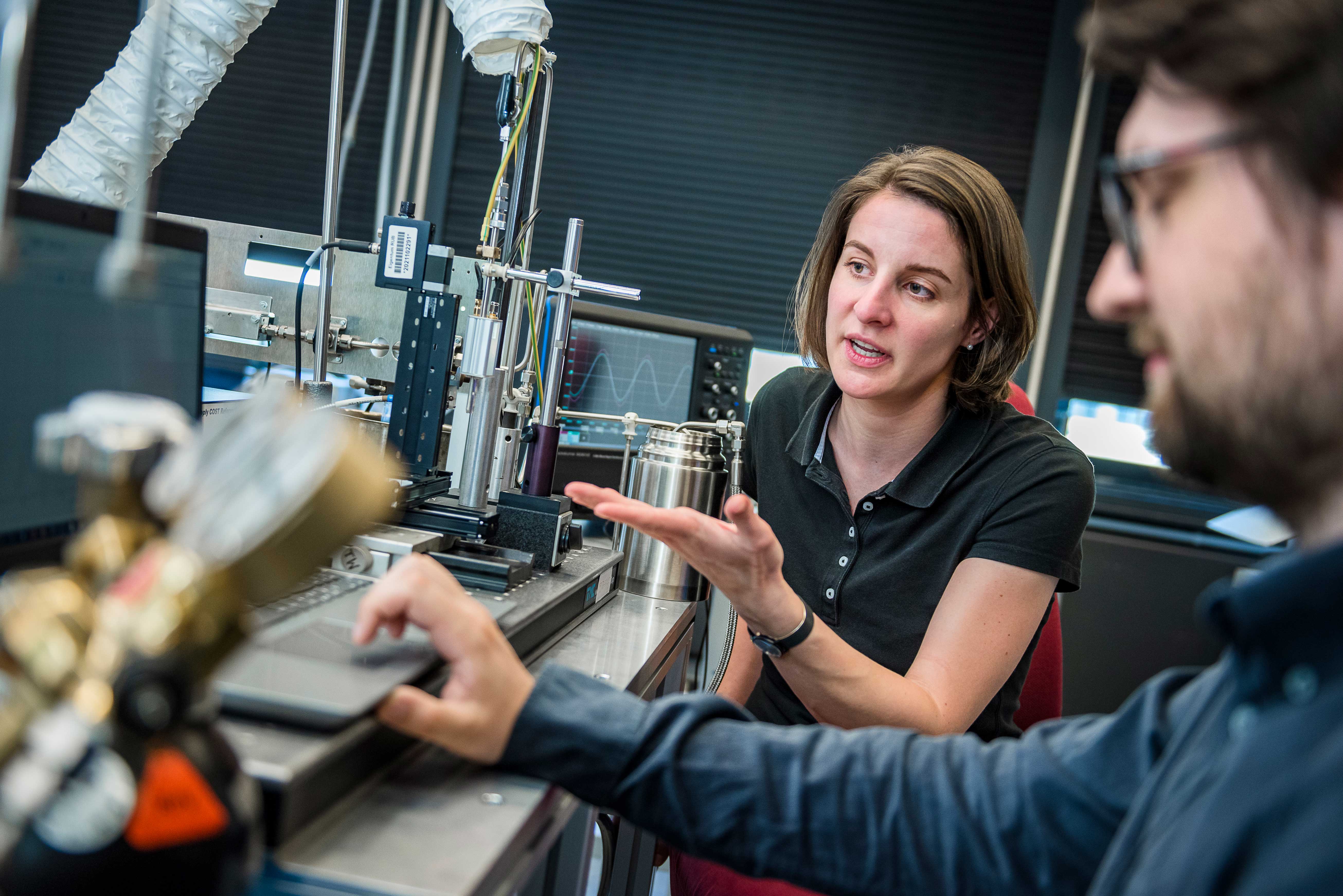

The areas of application for plasmas seem inexhaustible. In biomedicine, for example, the technology promises to heal chronic wounds better, kill antibiotic-resistant germs or treat cancer cells selectively. “There are many studies that show that plasmas could be useful for these applications,” says Professor Judith Golda, research physicist in Collaborative Research Centre 1316. “But in order to use plasmas for these purposes, we need to understand their underlying mechanisms.”

One problem is that while many studies have been done over the years, the techniques have not been comparable. “Making a plasma at atmospheric pressure is easy,” Golda explains. “All you really need are two wires to which you apply a voltage so that an electric field is created that ionises the gas between the wires.” Because it’s so easy, many research groups have built their own plasma sources. But not all plasma is the same. There are many properties that determine how suitable a plasma is for a particular purpose, such as the strength of the electric fields or the type and quantity of reactive particles it contains.

Complex plasma physics meets complex biological processes

Since both plasma physics and the biological processes that researchers want to manipulate with plasmas are very complex, it is difficult to explain the observed effects of plasma treatments mechanistically given the large number of variable parameters in plasma. In the early 2010s, therefore, the idea arose to develop a reference source, i.e. a plasma whose properties are precisely characterised and which can be reproduced with exactly these properties. The hope was that if different research groups used this plasma, they would know exactly which plasma parameters were responsible for certain effects. “Such a reference source already existed for low-pressure plasmas. We now wanted to transfer the concept to atmospheric-pressure plasmas,” recalls Judith Golda, who already worked on this issue while doing her PhD at RUB.

Together with partners from Greifswald, Eindhoven, Milton Keynes, York and Dublin, the Bochum group selected a plasma source that RUB physicist Dr. Volker Schulz-von der Gathen had already studied in-depth. “An important argument in our selection process was that many other groups worldwide have already worked with similar sources. So, we were looking for a plasma that could be used by the majority, so to speak,” explains Judith Golda.

Analyses at five locations yield the same results

The international team characterised the plasma source in detail. In the first step, the RUB researchers built five identical sources so that each cooperation partner could examine the plasma at their own location to ensure that it always had the same properties – which worked out well right away. The work took place within the framework of a funding programme of the European Cooperation in Science and Technology (COST). Thus, the researchers eventually dubbed their source COST-jet. Jet, because the plasma emerges from an opening in the form of a jet.

To make the plasma source available to all research groups worldwide, the project team wrote detailed assembly instructions and published them online at cost-jet.eu, where they can be freely accessed. “However, because it is sometimes not so easy for researchers without prior experience to implement such instructions, we also made sure that the COST-jet could be purchased ready-built at cost price,” points out Judith Golda. Sales are handled by Plasma Applications Consulting, a RUB spin-off.

Reference source deployed worldwide

Many groups worldwide are now using the COST-jet, so the research done by all these groups is comparable. Theoretically working groups complement this research.

“There are, of course, alternative sources,” says Judith Golda. “And they also have their justification, because you need different plasmas depending on the application.” Nevertheless, the research physicist is pleased that the reference plasma developed in Bochum is deployed at many plasma research locations around the world.

At RUB, too, research is ongoing in this field under the umbrella of the plasma Collaborative Research Centres. Groups from the fields of physics and electrical engineering are cooperating, for example, to understand in detail which reactive species form in the COST-jet and how their quantity changes with increasing distance from the source. “Depending on which gas you use, up to 1,000 different reactions can take place in a plasma in quick succession, because the reactive species interact in many combinations,” outlines Golda. The COST-jet is based on the noble gases helium and argon with small admixtures of other gases, for example oxygen and nitrogen. If these are dissociated and ionised in the electric fields, the atoms can take on all kinds of reactive forms: Oxygen, for example, can exist as a positively (O+) or negatively charged ion (O-), as a neutral atom (O), as molecular oxygen (O2) or ozone (O3). If nitrogen (N) is added to the mixture, numerous other combinations quickly emerge, for example NO, N2O, NO2 and others. “The reaction chemistry literally explodes,” as Golda describes the process.

Spectroscopic analysis of reactive species

The Bochum-based researchers were interested, for example, in how many reactive oxygen atoms are produced in the COST-jet and how their quantity decreases with increasing distance from the source. “Since many biological systems need a certain volume of atomic oxygen, plasma treatments with reactive oxygen species can have positive effects,” elaborates Judith Golda. “But sometimes it can be too much oxygen.” According to her, it is therefore important to know exactly how much reactive oxygen is present in the plasma and what the optimal distance from the target surface to the plasma would be. “This is the only way to later develop applications that are also safe for patients,” says the researcher.

Spectroscopy was used to make the necessary measurements. In the process, the researchers transmit laser light of a specific wavelength into the plasma. This light is absorbed by the oxygen particles, raising them to a higher energy level. After a while, they return to their ground state, emitting light of a certain wavelength, which the researchers can measure. The emitted wavelength depends on the particle that emits the light; a neutral oxygen atom, for example, sends back different light than a positively charged oxygen ion. Based on the amount of light emitted at certain wavelengths, the researchers can thus deduce the amount of different oxygen species.

We know pretty much what comes out of the source – that is only the case with a few sources.

– Judith Golda

This is how the team found that the amount of oxygen atoms in the plasma decreases exponentially as the distance from the source increases. Using analytical models, they also showed why this is the case. “Because the particles are so reactive, they quickly react further to form other compounds, such as molecular oxygen or ozone,” explains Judith Golda. The team is also researching the reactive species that result from adding nitrogen to the source, for example nitrogen monoxide (NO). This is particularly interesting for the researchers, because NO also occurs in the human body as a messenger substance and is important for wound healing. For example, they determine the flow pattern of NO molecules when they hit a surface from the plasma source.

Overall, the COST-jet is already very well characterised, according to Judith Golda. “We know pretty much what comes out of the source – that is only the case with a few sources,” she says.

adapted from Julia Weiler (RUB)

- Details

Achieving success together

One of the most interesting and important features of plasma medicine as a topic is its interdisciplinary nature, bringing together natural scientists, engineers and clinicians. The number of different scientific areas represented within the field has been continuously growing in the past ten years. This interdisciplinary environment has been a driving force behind clinical studies in a number of cases, wound treatment being a prominent example.

Over the next ten years, as plasma medicine continues to grow and attract new researchers, I expect this trend to accelerate and for the field to become even more interdisciplinary than it is today. This will bring new perspectives on existing questions, new therapeutic concepts, and novel research methods. I believe that these factors will be crucial for new scientific discoveries and the translation of emerging approaches such as plasma-based cancer therapy, into clinical practice.

by Julia Weiler (RUB)

- Details

Plasmas for all

Driving the plasma van to school

For many years, the plasma researchers at RUB have been committed to introducing plasmas to school students in different year groups. “Physics teachers sometimes conduct experiments that involve plasmas, but the word plasma doesn’t even appear in the curriculum,” explains Science Manager Dr. Marina Prenzel. In order to familiarise secondary school students with the concept of a plasma, the SFB team, in cooperation with Professor Heiko Krabbe and other physics didactics experts, has constructed various plasma experiments that can be stowed away in boxes and handily transported in a minibus. The researchers use them for interesting 90-minute workshops in sixth-form classes, where students can do their own experiments and learn about different applications of plasmas. “This is how we want to create awareness that plasmas are extremely important for many of our current technologies,” says Prenzel.

Students evaluate research projects

Students should not only be given the chance to learn what a plasma actually is and where it is used. Rather, the SFB team is also currently setting up a project in collaboration with the physics didactics department that aims at promoting the evaluation skills of adolescents and young adults. Here, students are to gain insights into various plasma research projects and evaluate which of these projects they would support. Another goal is to convey the significance of plasmas for the challenges of global warming.

More than 20 years of plasma summer school

For more than 20 years, plasma researchers at RUB have been organising an annual international summer school for Master’s students and doctoral candidates. It originally emerged from a European Erasmus project, acquired under the auspices of the Eindhoven University of Technology. When the funding ran out in 2000, the RUB team dedicated itself to continuing it. “The school is practically always overbooked,” says co-organiser Dr. Marc Böke. The 80 to 90 participants each year and the lecturers come from all over the world. The aim of the seven-day school is to give them insights into all the major technically relevant plasmas and, at the same time, to enable them to network with each other and with established researchers in the field. “Some of the former participants are now themselves running plasma labs,” says Böke. The RUB team hopes to resume the successful format soon, despite the coronavirus situation.

Virtual tours through plasma labs

Even though direct contact with the public is very limited during the coronavirus pandemic, the SFB team came up with a solution: The researchers made 360-degree recordings of their laboratories. This means that not only school classes, but also interested members of the public have the opportunity to take part in guided tours of the laboratories.

On 27 October 2021, the SFB 1316 team offers a virtual public tour free of charge. Registration is possible via email (

adapted from Julia Weiler (RUB)

- Details

Using plasma and electrolysis for CO2recycling

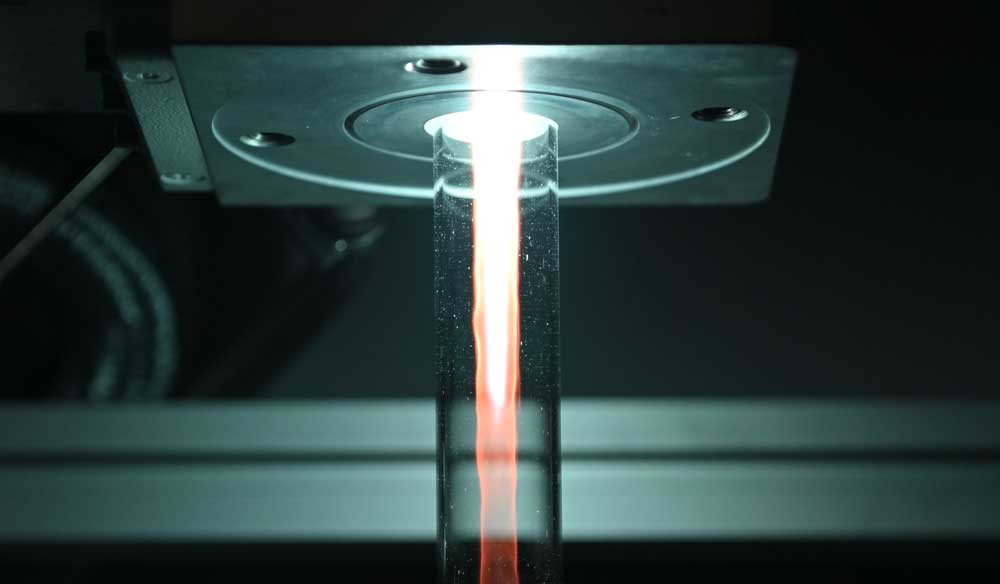

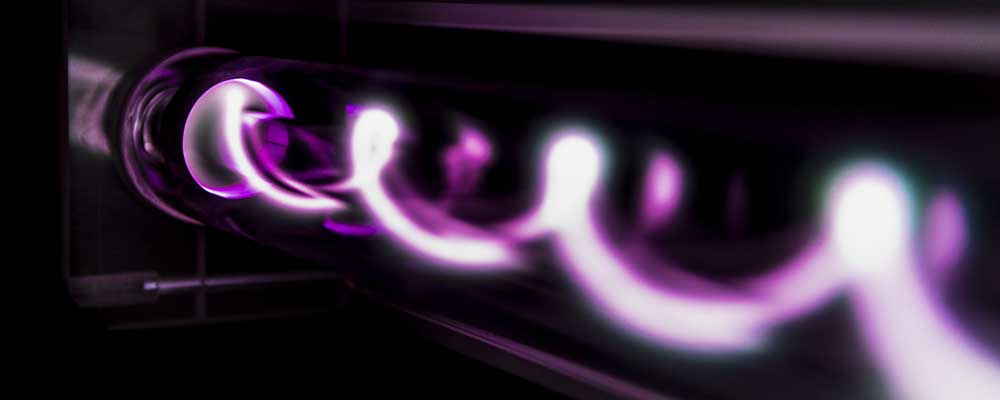

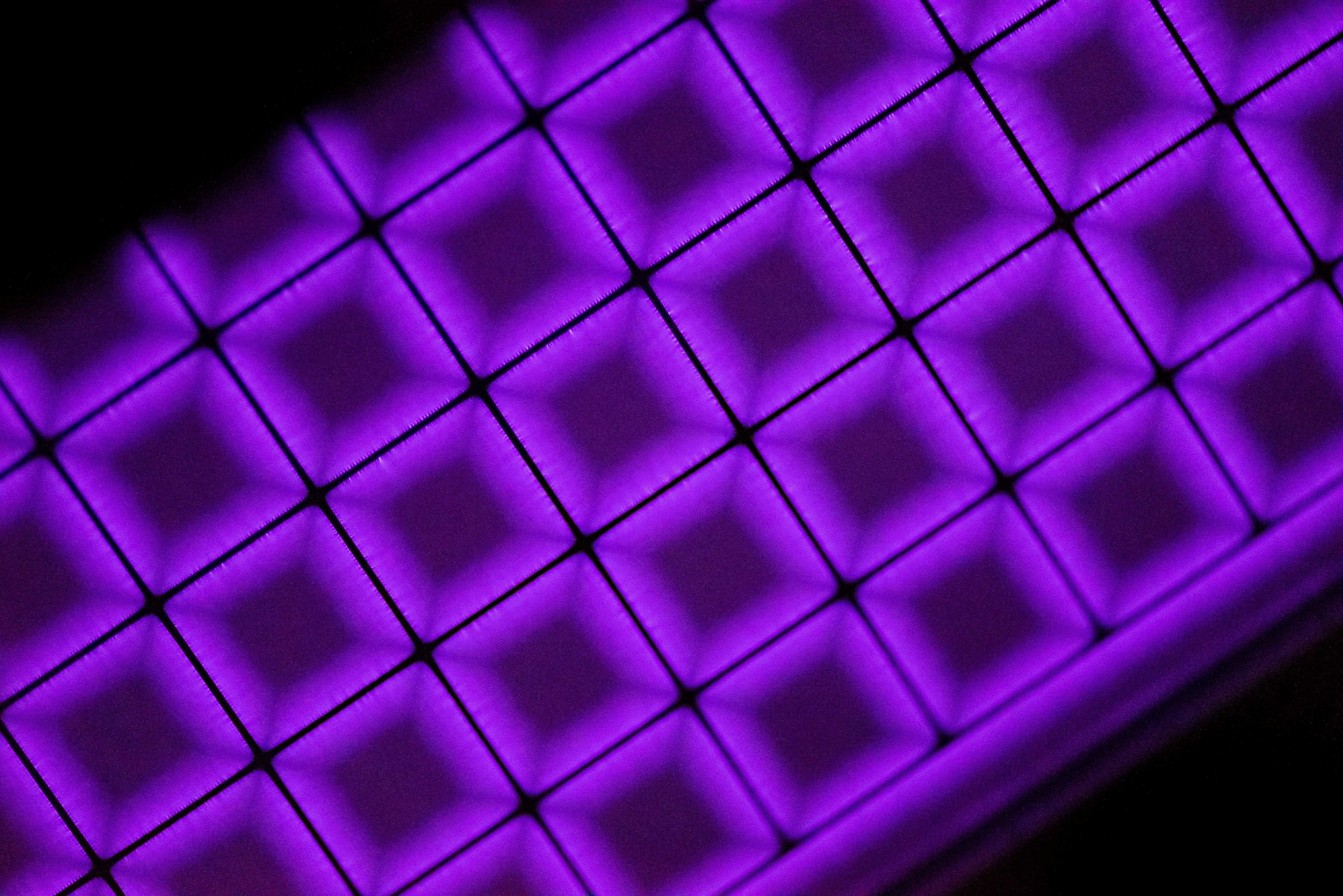

The plasma ignites with a bright flash and tears through the water for a few billionths of a second. Dr. Katharina Grosse from Collaborative Research Centre 1316 “Transient atmospheric plasmas – from plasmas to liquids to solids” (RUB) takes spectacular pictures that show the ignition process of plasma under water at high temporal resolution. Delivering the first data sets with very high temporal resolution, the researcher supports a hypothesis on the ignition of these plasmas: there is not enough time in the nanosecond range to form a gas environment. The nanosecond plasma ignites directly in the liquid. The particles created during ignition can interact efficiently with catalytic surfaces.

But how does the plasma ignite in these short time scales? What happens afterwards? Which substances are produced? And how is this ignition in the liquid possible in the first place? In her doctoral thesis, physicist Grosse explores these very questions. To this end, she applies a high voltage to a hair-thin electrode immersed in water for ten nanoseconds. The strong electric field thus generated leads to the ignition of the plasma. Using high-speed optical spectroscopy in combination with modelling of the fluid dynamics, the Bochum-based researcher is able to predict power, pressure and temperature in these underwater plasmas and, consequently, to explain the ignition process and plasma development in the nanosecond range.

Hotter than the sun

This is what she has observed: at the time of ignition, extreme conditions exist in the water. For a short time, pressures of many thousands bar are created; this corresponds to or even exceeds the pressure at the deepest point in the Pacific Ocean, as well as temperatures of many thousands degrees, similar to the surface temperature of the sun. “In addition, a power of several 100 kilowatts is consumed in the plasmas for a short time, which more or less equals the connected load of several single-family houses,” explains Professor Achim von Keudell, Grosse’s doctoral supervisor and head of the Institute for Experimental Physics II.

To achieve these measurement results, a complicated setup is necessary, which Katharina Grosse spent roughly a year on developing: “The electromagnetic interference is very strong and affects all measurement electronics. We had to build a large metal cage around the plasma chamber to bypass this source of interference. Another difficulty was to ensure the simultaneity of spectroscopic measurement and camera recording.”

Rendering plasma development visible

The tinkering has paid off: it is now possible to observe the plasma development very precisely. The recordings call into question the theory that has been common so far. Until now, this theory assumed that a high negative pressure difference forms at the tip of the electrode, which leads to the formation of very small cracks in the liquid with expansions in the nanometre range, in which the plasma can then spread. “It was assumed that an electron avalanche forms in the cracks under water, enabling the ignition of the plasma,” says von Keudell. However, the images taken by the research team from Bochum suggest that the plasma is “ignited locally within the liquid,” explains Grosse.

Tunnel effect under water

In her attempt to explain this phenomenon, the physicist uses the quantum-mechanics tunnel effect. This describes the fact that particles are able to cross an energy barrier that they should not be able to cross according to the laws of conventional physics, because they do not have enough energy to do so. “If you look at the recordings of the plasma ignition, everything indicates that individual electrons tunnel through the energy barrier of the water molecules to the electrode, where they ignite the plasma locally, i.e. precisely where the electric field is highest,” says Grosse. This theory has a lot going for it and is the subject of much discussion among experts. Subsequent experiments with negative pulses are to support Grosse’s tunnel theory.

Water is broken down into its components

The ignition process under water is as fascinating as the results of the chemical reaction are promising for practical applications. The emission spectra show that, at nanosecond pulses, the water molecules no longer have the opportunity to compensate for the pressure of the plasma. The plasma ignition breaks them down into their components, namely atomic hydrogen and oxygen. The latter reacts readily with surfaces. And this is precisely where the great potential lies, explains physicist Grosse: “The released oxygen can potentially re-oxidise catalytic surfaces in electrochemical cells so that they are regenerated and once again fully develop their catalytic activity.”

Underwater plasmas and electrolysis

How exactly is this going to be achieved? Can plasma and electrolysis be combined? RUB PhD student and chemist Philipp Grosse is looking for answers to these questions at the Fritz Haber Institute of the Max Planck Society in Berlin. “Electrochemical cells,” he explains, “help, for example, to reduce, recycle and convert carbon dioxide into useful chemicals. This requires a catalyst. However, during the electrochemical process, the catalytic surfaces wear out and lose their catalytic capabilities.” This is where the underwater plasmas studied by Katharina Grosse could provide a remedy and be used for material conversion at the electrode-liquid interface.

The brother and sister team intends to find out in what way underwater plasmas can be used in the electrolysis of chemical substances. How can the plasmas support electrolysis by changing the liquid and the electrode surface? How does plasma interact with the electrochemical cell? For this purpose, Katharina Grosse is setting up her experimental setup in Berlin, where her brother Philipp has been conducting research for two years. Instead of water, they use electrolytes as liquids, and a catalytic surface is built directly into the plasma chamber. The Grosses decided to use copper oxide in the form of nanocubes as a catalyst. These are nanometre-sized copper oxide cubes that are used as a catalyst for CO2 reduction. They then apply a high voltage to the electrode for a few microseconds. A plasma ignites. The changes observed in the copper cubes suggest that the oxygen produced by the plasma ignition activates the copper oxide. The initial measurements imply that the extreme plasma is indeed able to re-oxidise the copper cubes and thus regenerate the catalytic surface. Once the catalyst is ready for use again, the electrochemical cell should also work, and with it the CO2 reutilisation process. This would allow CO2 to be continuously converted into other products in industrial plants; the cycle would thus be closed.

The dream of an infinite electrochemical cell

In Bochum and Berlin, the researchers are already dreaming of an infinite electrochemical cell in which electrochemical processes alternate with plasma ignitions. But the Grosses still have a long and complicated way ahead of them. The greatest challenge at present is to combine the physical with the chemical structure so that plasma ignition and electrolysis can take place simultaneously.

The future of plasma technology

Should this succeed, it would be a “milestone, a technology with a lot of potential,” stresses von Keudell. The chemical industry is very interested in such a plasma process, according to the spokesman for the Collaborative Research Centre: “They have high hopes for the electrification of the chemical industry.” The advantages of plasma technology: it takes up little space, and the electrical energy can support the conversion of chemical substances at the push of a button.

adapted from Julia Weiler (RUB)

- Details

Transforming climate killers into raw materials via plasma technology

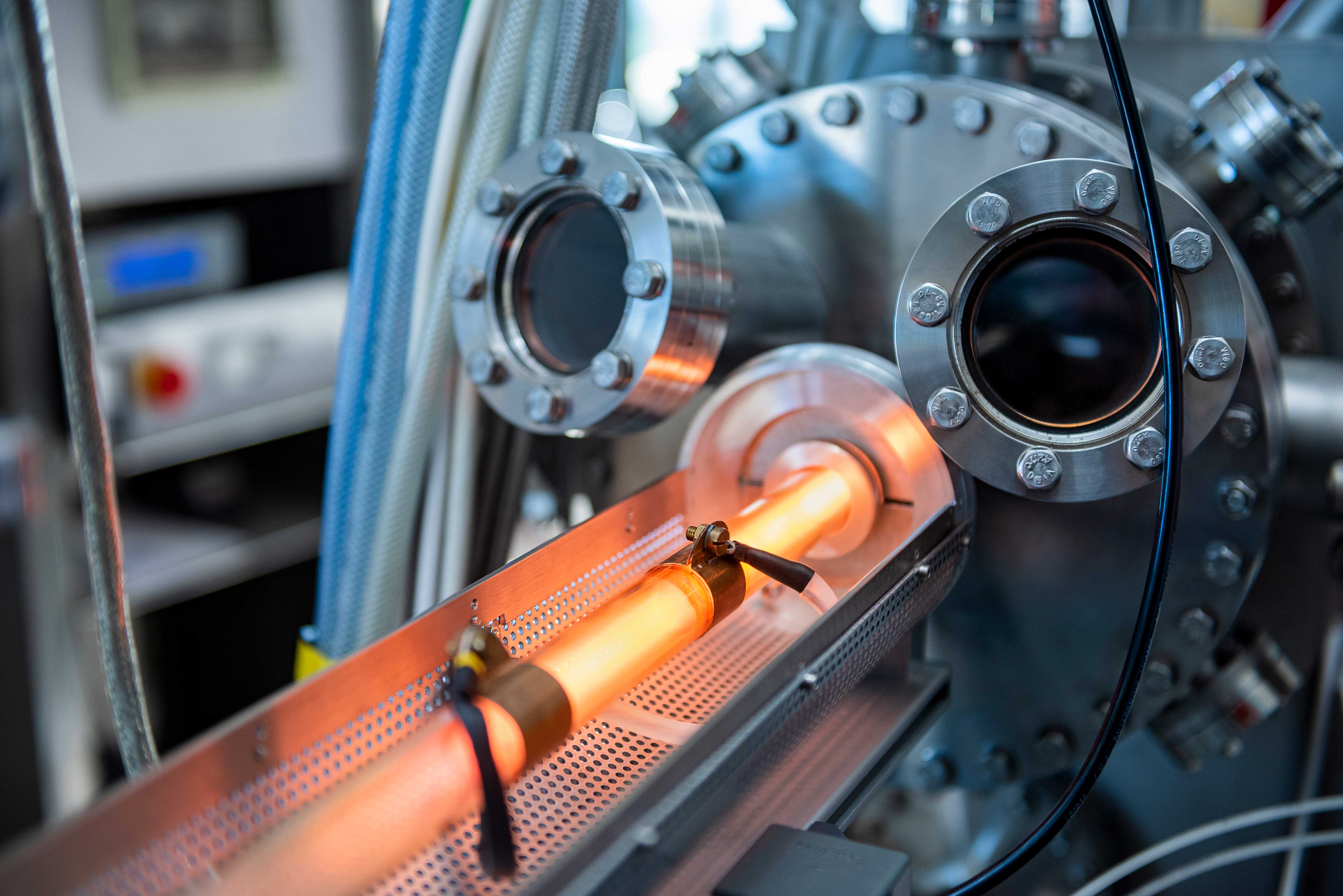

Hydrogen, oxygen, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide, methane – the steel industry releases a veritable cocktail of gases every hour. But how can these metallurgical gases be purified? This is where the research of Professor Peter Awakowicz from the Chair of Electrical Engineering and Plasma Technology and Professor Martin Muhler from the Lab of Industrial Chemistry comes in. The interdisciplinary research team at RUB studies how non-thermal plasma can be used for targeted cleaning and processing the metallurgical gas mixture. In the Carbon2Chem joint project funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), in which both researchers have been involved since 2016, they are testing their innovative plasma technology on real gases. “The combination of a basic research project in Collaborative Research Centre 1316 and an application-oriented BMBF project has been a long-held dream of both of us that we can now fulfil,” says Awakowicz.

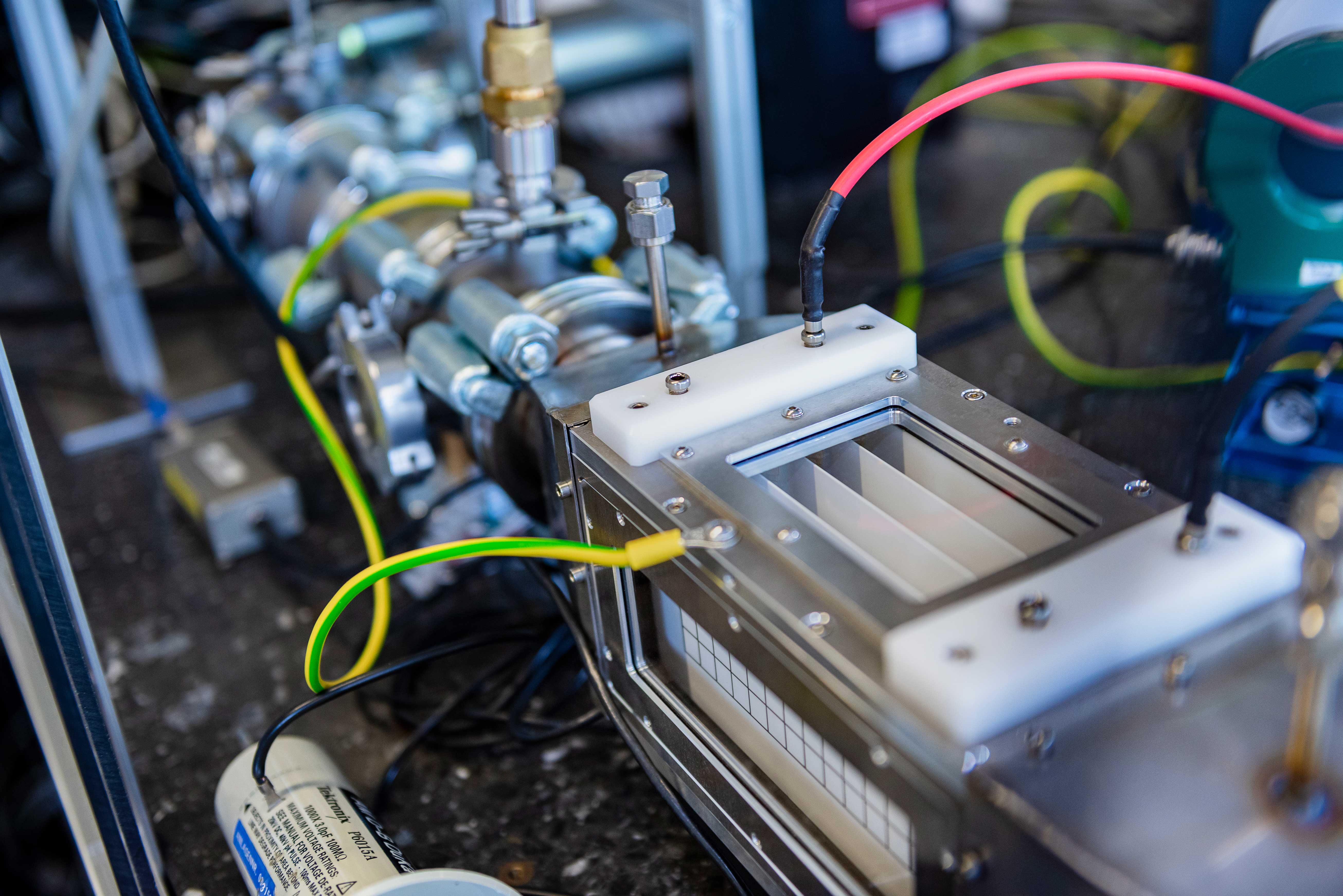

In sub-project L3 of Carbon2Chem, in which the RUB researchers are involved, the specific issue is pre-cleaning, the removal of oxygen from the coke oven gas. “This sounds simple, but it is tricky in detail,” explains research chemist Muhler. According to him, it is an intricate art to remove the oxygen from the predominantly hydrogenous coke oven gases. Traditional methods of exhaust gas purification, such as pressure swing adsorption, would not work if there was too much oxygen. The high chemical reactivity of oxygen would trigger dangerous gas reactions under normal pressure, such as an oxyhydrogen explosion. This is why Awakowicz and Muhler rely on pre-cleaning using plasma technology with cold plasma. How does it work? What makes non-thermal plasma so special? And how is it generated?

Innovative Technology for gas purification with cold plasma

Cold plasmas, or non-thermal plasmas, are plasmas in which the temperatures of ions, electrons and neutral particles vary. “The temperature of the electrons is high in these plasmas, while the temperature of the other gas particles is comparatively low,” explains Awakowicz. Since the plasmas are in thermal non-equilibrium, they are also often called non-equilibrium plasmas. They have an advantage with regard to gas purification processes: The ignited, cold plasma can be used for gas treatment without causing a significant increase in the temperature of the gas.

However, producing cold plasma is not easy. “The difficulty lies in supplying the gas with just enough energy so that the light electrons are accelerated and thus become hot, but the temperature of the large, heavy neutral particles and ions hardly changes,” explains Awakowicz. The research team from the Chair of Electrical Engineering and Plasma Technology has succeeded in producing precisely this state of non-thermal plasma in the purpose-built plasma reactor: The electrons become several tens of thousands of degrees Celsius hot, while the gas temperature of the entire plasma increases to barely more than room temperature.

“To achieve and understand this state, complex plasma diagnostics were necessary. We had to repeatedly readjust the individual parameters, such as the geometry and materials of the electrodes, the voltage amplitude and frequency, and associated with this the input power. Then the fundamental plasma parameters such as the electron density, the distribution function of the free electrons, but also the gas temperature had to be determined in order to optimise everything,” as Awakowicz describes the challenges.

While the team led by electrical engineer Awakowicz was fine-tuning the parameters for producing the cold plasma, the chemical researchers led by Muhler were analysing the chemical reactions triggered by the plasma discharge. It turned out that the cold plasma is so reactive that it animates the oxygen contained in the coke oven gas to react with hydrogen, so that water is formed. The gas mixture is freed from oxygen and is thus ready for further purification processes.

Waste gas purification on an industrial scale

What Awakowicz and Muhler have fundamentally researched in the RUB laboratory is being applied to specific gas mixtures in the steel industry in the BMBF Carbon2Chem project. In the first project phase from 2016 to 2020, the researchers already provided proof of feasibility: Their plasma technology can be applied to these specific metallurgical gases. In the second funding phase from 2020 to 2024, the technical processes will now be further validated and scaled up for industrial application from 2025.

Scale-up in the Carbon2Chem pilot plant

The relevant experiments take place on an area of 3,700 square metres in the pilot plant in Duisburg. The pilot plant was built in 2018 adjacent to the thyssenkrupp Steel Europe site and means that Carbon2Chem’s experiments can be conducted under industrial conditions. “The real exhaust gases are routed to the pilot plant site, where they are available to us,” explains Muhler. “We now have to show that our plasma system can operate with the real gases – on a much larger scale, of course. The reactor should be able to purify more than fifty times the amount of gas,” as he outlines the challenge. At RUB, the researchers have so far worked with small gas flows of ten litres per minute in the lab; at the pilot plant, they are dealing with flows with a much larger volume of 500 litres per minute and more. “A spectacular project, since the dimensions are so huge,” point out Awakowicz and Muhler.

Industrial implementation planned in 2025

The commercial implementation of the gas purification plant is scheduled for four years from now. “The final step, scaling up from tenfold to one hundredfold, will be an effort,” Awakowicz suspects, adding: “As researchers, we will have to hand over the baton to industry at some point.”

adapted from Lisa Bischoff (RUB)

- Details

Virtual public 360° tour of the SFB 1316

Insights into the projects and laboratories, the opportunity to take a look at the various experiments and diagnostics and ask live questions about them - this opportunity is available to everyone on 27.10.2021 at 4 pm during a virtual 360° tour. The tour is aimed at the general public and thus offers not only researchers and students but also interested persons outside of university the opportunity to experience research interactively and get to know the projects better.

- To participate in the virtual tour, registration is requested at

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .